Fungi are everywhere. In the air, in the water, in our bodies, in the trees, in the ceilings of our bathrooms, underground. They can be mushrooms (edible, medicinal, hallucinogenic, or very poisonous), or take other simpler forms, such as molds. They can trigger illnesses, but they can also produce antibiotic remedies, such as penicillin, or help ferment amazing cheeses and breads. Could they also be the future of packaging and building materials?

Fungi are nature's primary recyclers. They produce enzymes that aid in the degradation of organic matter, transforming it into minerals. Typically, these life forms grow best in shaded and humid environments. Like an iceberg, the visible portion of a fungus only represents a small fraction of it. Below the surface, for example, mushrooms develop long thread-like roots called mycelium. These are extremely thin white filaments that develop in all directions, forming a quickly-growing complex web. When the fungus is implanted in a suitable place, the mycelium behaves like glue, cementing the substrate and transforming it into a solid block. This substrate can be composed of sawdust, ground wood, straw, various agricultural residues, or other similar materials, which might otherwise go to waste.

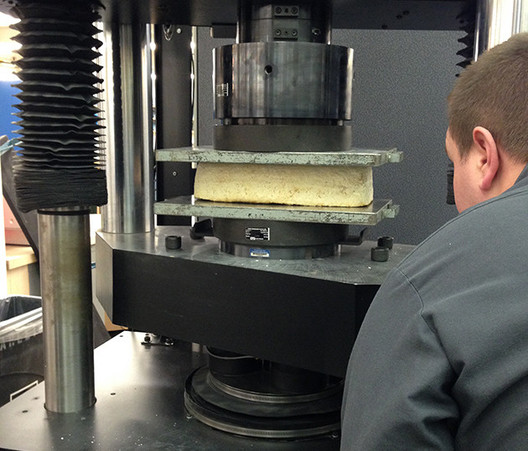

Depending on the mycelium strain and the substrate used, the final product can be molded to produce insulating panels, furniture, accessories, fabrics, packaging materials, and even bricks, with good thermal and acoustic characteristics and strong fire behavior. Scientific research [1] has shown that, in terms of physical and mechanical characteristics, mycelium-based materials resemble expanded polystyrene (often called Styrofoam), but with an improved level of biodegradability. “In addition to the lignocellulosic substrate, the characteristics of a mycelium-based biocomposite are strongly affected by the selected fungus species and their continuous growth. Thus, the consistency of the mycelium itself is, in turn, affected by the composition and structure of the substrate.”

Ecovative Design is a pioneer of mycelium-based design today, using this unconventional material to create objects such as packaging. To produce these objects, the substrate and fungi are combined in a solution and inserted into molds. After about 5 days of growth in favorable conditions – adequate temperature, humidity, and light – the material is solidified into the desired shape. The object then goes into an oven to completely deactivate the microorganisms present, allowing it be used as common packaging. Companies as large as IKEA and DELL have already begun using these packages, which are completely biodegradable.

The Living studio in New York worked in cooperation with Ecovative Design on the Hy-Fi Project, a pavilion that was built in the yard of MoMA PS1 after winning the MoMA's Young Architects Program in 2014. With ARUP's structural advice, mycelium bricks were developed, which grew in less than a week in prismatic molds from the residue of chopped corn stalks. When constructed, the bricks formed a tower about 12 meters high. At the end of the two-month exhibition, the tower was dismantled and the bricks were taken to composters, taking advantage of their natural biodegradability.

Carlo Ratti Associati, working in collaboration with the energy company Eni, developed an architectural structure made of mushrooms that was revealed at Milan Design Week. The “Circular Garden” is a series of arches composed of one kilometer of mycelium, wherein the spores were injected into an organic material to start the growth process. As many pavilions for temporary exhibitions generate a significant amount of waste, Jardim Circular follows a more sustainable course, with its constitutive mushrooms, ropes, and shredded wood chips returned to the ground after the end of the exhibition. The Shell Mycelium Pavillion, a collaboration between BEETLES 3.3 and Yassin Areddia Designs, similarly demonstrates alternative eco-conscious design through temporary structures. A wooden structure was covered with coconut marrow that contained the fungus. After a few days of care, the mycelium grew and formed a snow cover over the structure. The upper layer of growth died and hardened due to sunlight, forming a shell and protecting the lower layers.

In addition to architectural structures, mycelium also has potential for use in thermal and acoustic insulation. According to another initiative by Ecovative, live mushrooms packaged between wooden panels can form an effective insulating wall. In three days, the mycelium grows and solidifies loose particles to create airtight insulation, simultaneously adhering to the wooden boards and forming what is essentially an extremely strong sandwich. The result is similar to a structural insulating panel, but without thermal bridges. According to Ecovative, after about a month the mushroom insulation naturally dries out and becomes inactive.

But European researchers in the fields of computing, biology, and architecture [2] go a step further. They propose to develop a structural substrate using live fungal mycelium, together with nanoparticles and polymers, to make mycelium-based electronics through the implementation of sensory fusion and fungal decision making. “Mycelium networks will be computationally active, giving rise to entirely new biologically-based features for architectural artifacts and materials, such as self-regulation, adaptation, decision-making, growth, and autonomous repair - adding new advantages and value to architectural artifacts and the environment, and providing a radically alternative paradigm to state of the art 'smart buildings' that rely heavily on technical infrastructure. ”

Although we can gather some examples of initiatives in one article, the use of mycelium has still barely scratched the surface of its potential. Scientific articles on the subject almost always conclude with the statement: it is necessary to research heavily and experiment carefully with the material for it to have the efficiency, competitiveness, and industrial quality needed for mass use. But researchers also agree that there is enormous potential for the material in many diverse areas. Mycelium represents a paradigm shift in the way we approach the procurement, use, and disposal of construction materials. Being 100% biodegradable, found in abundance on the planet, “grown” from waste, and achieving excellent functional characteristics, mycelium-based materials have enormous, yet untapped potential. But, above all, mycelium also proves that great innovations do not necessarily require new technologies or complex materials. They may be closer than we think.

Notes

[1] Yangang Xing, Matthew Brewer, Hoda El-Gharabawy, Gareth Griffith and Phil Jones. Growing and testing mycelium bricks as building insulation materials. Earth and Environmental Science 121 (2018)

[2] Andrew Adamatzky, Phil Ayres, Gianluca Belotti, and Han Wösten. Fungal architecture. arXiv:1912.13262